12 DEBATES | AESTHETICS | CHANGE | ECONOMIES |

ECOSYSTEMS | ETHICS | NATURE | SCIENCE | SOCIAL SCALE

SOCIETY | SPIRITUALITY | TECHNOLOGY | TIME | CONNECTING | Refs

You may view/download this long page as a PDF!

Twelve debates: Aesthetics to Time

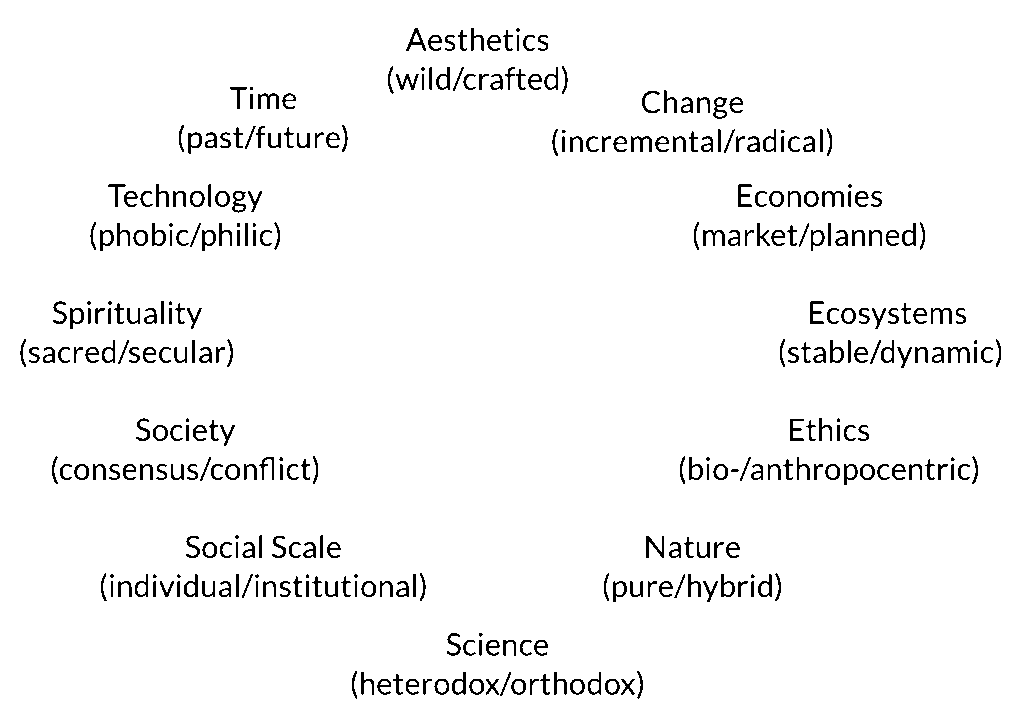

Axes are the building blocks of EcoTypes. Each addresses a fundamental consideration in how we approach environmental issues. Some may sound obvious, such as Ecosystems or Nature; many others, such as Change, Spirituality, Technology, and Time, may strike you as surprising. Yet thousands of completed EcoTypes surveys have suggested that each of these axes (capitalized here to differentiate from ordinary usage) is highly relevant to how we care differently about issues of environment.

There have been as many as eighteen EcoTypes axes. At present there are twelve, to be summarized below. The statistical reasoning behind these twelve is explained via EcoTypes themes, but there was a learning-related reason as well: eighteen axes are a bit too many to understand! You’ll nonetheless find these twelve axes to suggest the considerable conceptual breadth of EcoTypes. The ways we care differently about issues of environment are by no means limited to what people generally think of as “environmental” considerations!There can be differing opinions on each, quickly summarized, and measured in the Ecotypes survey, via contrasting axis poles. The EcoTypes survey includes two statements for each axis, one summarizing each pole, for which the respondent moves a slider between them to represent their position. These two statements were statistically selected from previous versions of the survey (which originally included eight statements per axis!), to balance the breadth and complexity of EcoTypes axes with survey doability.

Your EcoTypes survey report includes your average score for each of the twelve axes. If you haven’t yet taken the survey, make sure and do so, possibly after reading the below to inform your survey opinions.

A brief summary of each axis, and one popular or scholarly disagreement as summarized via its axis poles, is below. Do take these disagreements seriously!: it’s too easy simply to say that you see both sides.

Approach these disagreements as representing genuine differences among people. You may find yourself strongly inclined toward one pole or the other; or, you may find yourself somewhere in the middle—that’s okay. But, no matter where you position yourself, try hard to respect the differences implied in each axis.

Aesthetics

Is beauty primarily to be found in untouched, wild nature, or in landscapes crafted by humans?

When you close your eyes and imagine something beautiful, what do you see? You probably might imagine many things. How about landscapes: do you imagine a stately old forest? a well manicured garden? an orderly suburb? a wild riot of weeds blooming on the side of the road? One of the ways we approach issues of environment involves their aesthetic appeal: we are drawn to landscapes, and related environmental solutions, that look beautiful. But maybe a good environmental solution involves considerable human manipulation, which may not appear beautiful to you. The EcoTypes Aesthetics axis probes our fundamental assumptions about beauty, via the poles of wild vs. crafted landscapes.

In the long history of aesthetics, the study of beauty, there has been an overriding emphasis on human art and artifice; yet over the last several centuries, aesthetics has also moved into the realm of the nonhuman (Carlson 2016). Perhaps due to this bifurcated history of aesthetics, and also due to the place (and displacement) of nature in our broader history of ideas, environmental aesthetics has forever struggled with the question of whether beauty requires art, and thus a (human) artist fashioning the landscape, or whether there is something singularly beautiful in unmanaged, untamed nature.

When aesthetic appreciation of the nonhuman realm returned in roughly the mid-18th century, it did so with a heavy dose of natural theology, a long-favored doctrine that nature is a book like the Bible which humans could read to understand the beauty, mystery, and power of the divine (Glacken 1992). Glacken’s summary of this era nearly 300 years ago suggests characteristics that do not sound entirely foreign today:

It was an age in which sensitive poets, travellers, ordinary people alike unashamedly watched, became lyrical, and described as best they could waterfalls, cataracts, mirror lakes, lonely crags and precipices, Alpine scenery, winding roads, panoramic views, solitary plains, strolls along the seashore with spires in the distance (Glacken 1992, 110).

Other vestiges of 18th-century environmental aesthetics are evident today as well. One is the distinction scholars have made between the sublime and the picturesque (Carlson and Zalta 2016). The picturesque is an aesthetic experience of nature as picture-like—much as Kodak picture spots were once located on many US national parks, designating just the right location and perspective to apprehend beauty. In contrast, the sublime was a much less domesticated, much more fearsome apprehension of the nonhuman—as William Cronon has written in an essay on wilderness,

Sublime landscapes were those rare places on earth where one had more chance than elsewhere to glimpse the face of God (Cronon 1995a, 11).

Indeed, the spiritual and religious connotations of landscape aesthetics as summarized by Glacken and Cronon led to real implications for landscape protection; as Cronon continues,

God was on the mountaintop, in the chasm, in the waterfall, in the thundercloud, in the rainbow, in the sunset. One has only to think of the sites that Americans chose for their first national parks…to realize that virtually all of them fit one or more of these categories. Less sublime landscapes simply did not appear worthy of such protection (p. 12).

One can (as Cronon did) trace a direct line from historical veneration of the sublime to contemporary veneration of the wild and wilderness, whereas the picturesque followed a rather different route, perhaps because the human hand, at least a human framing of the view, was always evident. Thus two recent volumes in environmental aesthetics are The Aesthetics of Natural Environments, and its companion, The Aesthetics of Human Environments (Carlson and Berleant 2004; Berleant and Carlson 2007).

Contemporary environmental aesthetics very much seeks to expand this boundary of beauty to embrace, at least consider, human-fashioned landscapes; thus, the final section of Environmental Aesthetics: Crossing Divides and Breaking Ground (Drenthen and Keulartz 2014) is titled “Wind Farms, Shopping Malls, and Wild Animals,” and among other important recommendations for environmental aesthetics in future, Yuriko Saito endorses “artefacts, human activities and social relationships,” including mundane objects constructed from the physical world and active human engagement with the nonhuman beyond the (Kodak moment) view (Saito 2010, 373).

Yet there are other contemporary movements in environmental aesthetics that celebrate the wild. Some date back to Aldo Leopold’s famous dictum from Sand County Almanac that

A thing is right when it tends to preserve the integrity, stability, and beauty of the biotic community. It is wrong when it tends otherwise (Leopold 1949, 242; emphasis added; see also Simberloff 2012).

One source of continued aesthetic inspiration in wilder elements of nature has, perhaps ironically, been science. E.O. Wilson, famous for his role in inventing sociobiology, has written extensively on how biological adaptation can provide a scientific basis to understand human aesthetics as well as ground environmental protection in biophilia (Wilson 1998a; 1998b; 2009). Dutton (2003) has provided a more nuanced, yet supportive, review of this biological grounding for aesthetic appreciation of nonhuman nature. Yet anyone familiar with debates over sociobiology knows that there are many critics of this view as well.

The Aesthetics axis, via its wild vs. crafted poles, invites you to reflect on what you consider to be beautiful, and to situate your own aesthetics in the deep history and continued debate around beauty beyond the purely human realm.

Change

Can we achieve desired environmental change incrementally, or is more radical change needed?

Most of us desire change in our world: we are, understandably, unsatisfied with how things are. How do we achieve large-scale change? You may feel that the little things you do can help achieve big change, if enough people do them. Or, you may feel that the little things we do may not amount to anything, that real changes can only be achieved by changing the system. The EcoTypes Change axis gives us an opportunity to explore our assumptions about change, via its incremental vs. radical poles.

A great deal of environmentalism and environmental scholarship are about change, focusing not only on the policies to achieve desired changes, but on what sort of change we need. The realm of change is a complex one, prompting one recent publication to discuss fully fifteen common claims related to environmentally significant social change, such as “Change just happens” or “Buy green, be political” (Maniates and Princen 2015).

Running through many discussions about change is a fundamental debate over whether or not this change can happen incrementally. Many scholars believe that, ultimately, some very big changes need to take place if we wish to successfully address environmental issues; but it’s quite possible that we can achieve these changes step by step. A good example in the environmental realm is the notion of climate stabilization wedges, grounded in the argument that “Humanity already possesses the fundamental scientific, technical, and industrial know-how to solve the carbon and climate problem for the next half-century” (Pacala and Socolow 2004, 968). Their position is that the very large reductions in fossil fuel emissions needed to stabilize climate—which could be visualized as a big triangle denoting the space between the current and desired trajectory of emissions—can be achieved via many incremental contributions, each a smaller wedge adding up to this big triangle, such as vehicle efficiency, CO₂ capture, or conservation tillage.

Incremental change could also be supported via notions of tipping points (Gladwell 2000), whereby certain small changes result in social epidemics similar to disease outbreaks. Tipping points have reportedly been observed in a wide range of phenomena ranging from crime reduction to the popularity of a novel; applying tipping points to positive environmental changes, it is possible that individual-scale action—arguably limited to incremental change at its inception—could actually result in much larger change once it achieves a critical threshold.

Incremental change approaches are widespread and popular—as but one measure, the Pacala and Socolow paper mentioned above has been cited thousands of times, as has been Gladwell’s Tipping Point. This support for incremental change is understandable: why not start with what can readily be done, even if these step by step actions don’t in themselves fully achieve desired environmental outcomes? Yet there can be several possible critiques of this incremental change approach, which suggest that more radical change is needed.

The most obvious critique of step by step change is that, like many politically expedient approaches, it may not accomplish much, and in fact may lull us into a business-as-usual approach that avoids more fundamental changes. In this respect, critiques of incremental change are similar to critiques of the individual Social Scale pole (e.g., in the context of sustainability; see Swyngedouw 2010) in arguing that political formations such as neoliberalism constrain our imagination of what is possible and needed. These arguments may challenge widespread incremental-change college efforts such as the campus sustainability movement (with related organizations such as AASHE), which often proceeds, one institution at a time, in a politically acceptable manner that assumes rather than questions the norms of higher education (Wals and Jickling 2002).

These critical perspectives also shed light on possible relationships between our views about change and the optimal social scale of change (see Social Scale axis). For instance, many popular discussions today focus on individual-scale action and incremental change, in contrast to other discussions (also popular among some environmentalists) that focus on institutional-scale action and radical change (e.g., Jensen 2006; Klein 2014). Logically, however, these axes may be joined in multiple ways: for instance, you could believe in incremental change yet support institutional social scales of action.

Reflect for a moment on environmental conflicts such as those mentioned above, and you’ll discover assumptions about change in each. In the context of downstream conflicts such as struggles over forests or toxic site cleanup, these assumptions may seem less evident, as the Change axis primarily concerns our broad approach to making a difference; but you will still hear echoes of radical change in the frustrations some activists express at what they see as the painfully slow (read: incremental) efforts to address these place-based conflicts. Certainly you can hear incremental vs. radical change expressed in debates over upstream environmental conflicts: can we, for instance, successfully address climate change by tinkering with policy step by step, or is radical (some might say visionary; incrementalists might say impossible) legislation required?

This summary offers some context on the incremental vs. radical Change poles. More broadly, the Change axis serves as a reminder for us to reflect on our assumptions about how to achieve true and lasting change, if we want to make a difference in this world.

Economies

Do economies ideally achieve environmental protection via free markets,

or are planned economies and regulation best?

Some of us embrace capitalism; others are suspicious of capitalism, perhaps especially in an environmental context. Where are you along this spectrum of opinion? Your feelings about capitalism may indicate what sort of an economy you prefer, and though it’s hard to imagine a global economy totally devoid of capitalism, there is a spectrum of economies that people debate in the context of environmental benefit. The EcoTypes Economies axis helps us explore this debate, via its market vs. planned economy poles.

The EcoTypes Economies axis addresses differences in what a green, environmentally friendly economy would look like. You might think the answer is obvious: economies that favor careful planning and regulation with environmental impact in mind are clearly the most ecologically friendly (Gunningham et al. 1998; Layzer 2012). But there has been vigorous pushback by economists and legal scholars who argue that regulation can actually impede environmental progress (Huffman 1994; Levine 2010). And the very distinction between market and planned economist requires clarification. At heart, the Economies axis suggests that important differences people have related to economic systems matter in how we approach issues of environment.

Purely planned economies are rare. The term is often used the limited sense of command-style economies of the Soviet era or earlier decades of development in China, of which only a few remain in today’s world, especially following the dissolution of the USSR (Marer et al. 1992). In theory, planned economies allocate goods and services, and invest in factors governing production and consumption, in a centralized manner, generally along lines of state political control. In a broader, less formal sense, planned economies are those that receive relatively more guidance from the state, in the form both of incentives and regulations, than those of a more free market orientation, and under this broader conception a number of countries of the world tend toward a planned economy.

One example of planned economies in this broader sense might be the countries of western Europe, also market oriented but with a reputation for planning and generally better environmental outcomes. In comparison, the United States has generally embraced the rhetoric of a free market orientation. While clearly applicable in these cases, differences between planned and market economies are less clear in others, especially in countries transitioning from planned to market economies (Milanovic 1998), or those seeming to embrace both. A good example is China, which in recent decades has moved toward full participation in—if not near command of—the global market economy. Yet its doctrine of a circular economy suggests that China retains a strong emphasis on planning and regulation—and emphasis on environmental benefits (Zhijun and Nailing 2007; Yuan et al. 2008; Su et al. 2013; Mathews and Tan 2016).

If purely market- or planning-based economies are difficult to identify today, there remain arguments on both sides as to which might result in environmental benefits (Blumm 1992; Moroney and Lovell 1997; Sunstein 1997; Moosa and Ramiah 2014). In particular, some economists have championed free markets as, perhaps ironically, the best way to achieve environmental progress (Anderson 2019). Free-market environmentalism takes several forms, but a key component of the argument is that markets remain the most efficient means of allocating economic effort, and given the environmental benefits of efficiency—say, minimizing waste in raw materials, conserving energy, controlling pollution with minimal cost, etc.—the free market, unfettered by excessive regulation, is actually a greener approach. While reviews of these arguments are mixed, one must minimally concede that both planned and free-market economies have their environmental advocates.

It would seem possible to test the efficacy of more free-market vs. planned economy approaches via the actual environmental performance of countries that lean one way or the other. The Yale Environmental Performance Index (EPI) offers one comparative window into country-by-country environmental performance, including a number of measures relating each country to environmental health, ecosystem vitality, and climate change (Hsu and Zomer 2016; Block et al. 2024). The EPI aggregates countries by region, level of economic development, and common economic characteristics. In these respects, recent EPI results suggest that countries of the global West, many of which involve advanced market economies with relatively high levels of planning and regulation, are doing the best job of environmental performance overall, while those in southern Asia and sub-Saharan Africa are doing the worst. These regional differences, however, seem less to break down along lines of a market vs. planned economy than shared historical development trajectories in these regions. The EPI also considers drivers of environmental performance, including economic drivers related to market orientation, and governance drivers related to planning/regulation: their findings suggest that both are relevant, though differences emerge in their significance vis-à-vis environmental health, ecosystem vitality, and climate change.

A larger picture of how economic systems relate to issues of environment must include the global phenomenon of neoliberalism, perhaps one of the most powerful forces transforming our world over the last half century (McCarthy and Prudham 2004; Harvey 2007; Castree 2011). In general, neoliberal trends among states of the world have resulted in reductions in environment-related planning and regulation—a devolution of power from states to corporations with emphasis on free markets and privatization. Has neoliberalism been a net environmental negative? On-the-ground studies suggest so, though there are indications, as argued above, that market-based incentives and looser regulatory strictures have in some cases cultivated benefits to nonhuman nature and environmental health. And more recent indications suggest that antiglobal populist movements are undermining neoliberalism (Brown 2019; Cayla 2021): is protecting national interests the new planning thrust of economies in many countries of the world? If so, populist economies do not have a strong environmental record (Ofstehage et al. 2022); is this the fault of their planned or their market characteristics?

Preference for the market vs. planned Economies poles may be a surrogate for political identification: in the U.S., for instance, the free market is frequently touted by the political right, and planning/regulation by the left. Yet differences among countries of the world in how they mix market and regulatory incentives, thus where they reside along the span of these Economies poles, may well be environmentally relevant. The Economies axis thus invites further discussion around these differences in how we organize our economic activities in the context of environment.

Ecosystems

Are Earth and its ecosystems inherently stable, with change arising from human disturbance, or are they more dynamic over time?

Do you feel that stability and balance are the norm for Earth’s ecosystems? Before humans showed up on our planet, do you imagine a world in which ecosystems were in harmony? Many of us do. But ecological science has recently posited that change, not stasis, may be more how ecosystems work, even in the absence of human perturbation. And these two pictures of Earth’s ecosystems may affect your views on environmental issues: are you, for instance, inspired by calls to restore balance in damaged landscapes? The Ecosystem axis gives us an opportunity to consider our assumptions about how nonhuman species and habitats work, via its static vs. dynamic ecosystem poles.

The question of whether stability or dynamism best characterizes ecosystems is an eminently practical question in the environmental context, as it profoundly relates to how we view human impacts, our goals for ecological restoration, and ultimately the place of humans on Earth. The Earth has, of course, changed in many ways before people arrived on the scene; that much is not controversial and has been long documented, with ecosystem effects detailed via the field of palynology (e.g., Davis 1969).

But what about changes more on human timescales? Typically we think of those wrought by human forces, such as the longstanding reality of deforestation or the more recent reality of anthropogenic climate change. These very significant human impacts could lead to the conclusion that change—especially change for the worse—is always of human origin, and that Earth and its ecosystems would otherwise remain in a state of equilibrium and harmony if human impacts were eliminated.

Indeed, some classic notions in ecology seem to favor this balance of nature thesis. One is the idea of ecological succession and the related concept of a climax community. Succession is often presented via the example of a forest, starting with major disturbance such as fire that removes the forest and effectively starts the cycle of succession via early seral stage species. In time, succession is understood to produce a stable, climax state dominated by later seral stage species and effectively in equilibrium until another major disturbance arrives. The overall picture, then, is one in which equilibrium is the rule and disturbance the exception—and at any rate, equilibrium is eventually restored following disturbance.

More recent approaches to ecology, however, have stressed disturbances as integral to the structure and function of many ecosystems. Here, change is the rule and stasis the exception, as a wide range of biophysical processes—fire, weather events, earthquakes, insect outbreaks, etc.—result in episodic or recurrent drivers of change. Following these approaches, ecosystems and their constituent species are thus continually in a state of dynamic response to disturbance.

The resultant picture emanating from disturbance ecology (Meurant 2012) and related work in nonequilibrium ecology (Rohde 2006) pose a fundamental threat to the longstanding assumption of the balance of nature. As one early commentary (Tarlock 1994) summarized this challenge:

Legislators, regulators, resource managers, and lawyers have derived a powerful and general lesson from ecology: Let nature be.…Legislatures and lawyers enthusiastically embraced [the equilibrium/balance of nature] paradigm because it seemed to be a neutral universal organizing principle potentially applicable to the use and management of all natural resources.…Twenty-five years after this paradigm was incorporated into law, it…is now unraveling (pp. 1121-22).

Yet ecosystems are not simply in a state of constant, random flux—leading scientists to more precisely define what stability would mean in ecosystems (e.g., Pimm 1991). One comprehensive literature review (Grimm and Wissel 1997) included fully “…163 definitions from 70 different stability concepts and more than 40 measures” (p. 324). What emerges from this rich literature is, first, a critique of any simple notion of stability in such a complicated, multifaceted reality as an ecosystem; and second, a variety of ways to characterize dynamic patterns in ecosystems.

Then there is work by ecologists on the dynamic notion of resilience, possibly more helpful than concepts (e.g., sustainability) grounded in an equilibrium approach to nature. Resilience gets us back to the practical significance of change: if indeed disturbance and nonequilibrium—whether due to anthropogenic or biophysical drivers—are a part of Earth and its ecosystems, then how do we manage ecosystems to ensure that these changes do not result in degradation? A wide range of theories, publications, research efforts, and conferences dedicated to resilience, grounded in classic work by ecologists (e.g., Holling 1973), suggest possibilities to care for Earth and its ecosystems without resorting to earlier notions of the balance of nature, yet with appropriate attention to changes of concern, such as catastrophic shifts in ecosystem regimes (Scheffer et al. 2001; Scheffer and Carpenter 2003).

Ultimately, this discussion suggests the need for us to grapple with the reality of ecosystem dynamism. Certainly, change has occurred in ecosystems as a result of human causes (Vitousek et al. 1997; Nelson et al. 2006). As one of many examples, anthropogenic drivers are changing ocean ecosystems in fundamental ways (e.g., Jackson 2001; Orth et al. 2006; Halpern et al. 2008)—yet biophysical drivers are still evident (Di Lorenzo et al. 2008; Yasuhara et al. 2008).

The tension between stable vs. dynamic Ecosystem poles suggests that human impacts on Earth and its ecosystems can certainly be, but are not always, negative; that ecological management may involve more than just returning ecosystems to some stable, preexisting state of equilibrium; and that dynamic concepts of ecosystems such as resilience suggest a different, more active, positive role of humans on Earth.

Ethics

Should we care about the nonhuman world for its own sake, or for how it serves human interests?

The EcoTypes phrase “many care, just differently,” applies directly to the Ethics axis. You clearly know what you care about, but why do you care about these things? Ethics gets at not just what we care about, but why. In the realm of environment, why would you say you care? You may think of how you grew up, or some life experiences you have had—say, time outdoors, time working the land, or maybe mediated experiences like nature programs or dire news predictions. You may initially feel that it’s obvious why you care, when you think of a serene experience near a lake; but ethics probes this why question more deeply and systematically. The EcoTypes Ethics axis offers you an opportunity to process these experiences, to get to the why of your caring, via two poles that summarize arguably divergent, broad ways of caring: anthropocentrism and biocentrism.

People can care about the nonhuman world for a variety of reasons. One key motivation concerns how we value nature: though there are many possibilities, two broad value categories long discussed and debated in environmental philosophy include anthropocentrism and biocentrism. Most generally, anthropocentric ethics value nature as a means to human ends, whereas biocentric ethics value the nonhuman world independent of its service to humans. The distinction between the two has been championed by environmental movements such as deep ecology, which favors a broadly biocentric (deep) approach to nature in contrast with what some argue is a shallow, anthropocentric approach (Naess 1973). Other classic environmental publications (e.g., White 1967) have similarly indicted anthropocentrism as the fatal flaw in western ethics and religion that justified our long mistreatment of the nonhuman world; some have even argued that nature is worthy of moral rights similar to humans (Nash 1989). Are these critiques of anthropocentric ethics correct?

A deeper understanding of the difference between anthropocentric and biocentric ethics can be gained by thinking more carefully about value. One key distinction in ethics is that between extrinsic and intrinsic value. Intrinsic (also called inherent) value implies that we value something in and of itself. This form of value has, in most systems of human ethics, been invoked to justify our moral obligations toward, say, infants and disabled persons who don’t necessarily serve the needs of others. Extrinsic (also called instrumental) value implies that something is valuable not in and of itself, but with reference to others who possess intrinsic value. Most people possess both intrinsic value (just because they are people) and extrinsic value (as serving the needs and desires of other people).

This is getting abstract! Let’s consider extrinsic and intrinsic value, and their related anthropocentric ethics, in the context of environmental issues. As noted above, many argue that human-environment relations have largely been premised on anthropocentrism, the notion that humans alone possess intrinsic value, while nature has typically been valued instrumentally (extrinsically) in service to humans. Based on these ethical assumptions, actions such as air and water pollution abatement can be justified given clear human benefits, whereas actions such as biodiversity conservation or ecological restoration can be more difficult to justify unless they are shown to convey human benefits such as ecosystem services. A biocentric (also sometimes called ecocentric) approach would accord the nonhuman world intrinsic (as well as extrinsic) value, thus potentially justifying a wider range of environmental actions (including for instance conservation and restoration) without necessary reference to human ends.

The relative merits and practicality of anthropocentric vs. biocentric ethics were heavily debated by environmental philosophers several decades ago, with some (e.g., Callicott 1984) critiquing anthropocentrism and others (e.g., Norton 1984) defending more refined anthropocentric approaches. In the intervening period, some have continued to argue, against the defenders of anthropocentrism, that this ethical approach is insufficient for human-environment relations (e.g., Westra 1997; McShane 2007), while others have argued, partly in favor of anthropocentrism, that this and other theoretical debates are generally not useful, since for instance people of differing value systems can nonetheless agree on many important environmental actions—a position sometimes called environmental pragmatism (Light and Katz 1996). Some have simply applied these ethical categories to interpret major environmental controversies (e.g., Proctor 1999), while others have examined the relative influence of anthropocentrism and biocentrism in popular environmental movements such as sustainability (Shearman 1990; Williams and Millington 2004).

Overall, though, this debate has received relatively less attention in recent years than it did several decades ago, not so much because it is unimportant but perhaps because scholars have not generated many new insights. If anything, recent literature has either assumed or reiterated the significance of the debate (Kopnina et al. 2018), though some work indeed challenges the distinction, in the context of contemporary environmental movements such as environmental justice (Hobson 2004). And additional moral theories are possible: one example is theocentrism, a position that grounds moral action in Earth as a sacred creation of God (Hoffman and Sandelands 2005; Grasse 2016). The biocentrism vs. anthropocentrism debate, and poles of the Ethics axis, remain important as a way for us to reflect on why we care about environmental issues, so as to be clear as to our ethics. As with other axes, it might seem easy to elide the distinction, arguing that both are important. But this approach may be based on a shallow understanding, say of anthropocentrism as caring more for humans than nonhumans, and vice versa for biocentrism. The distinction between these two Ethics poles lies not in what we care for, but why we care: one can care a great deal for nonhuman nature extrinsically as well as intrinsically. To some, this may render the distinction moot: so long as we care, they may say, who cares about why they care? But, at least to clarify the EcoTypes proposition that many care, just differently, the Ethics axis may be a clear marker of the differing ways we care.

Nature

Is nature typified by its own inherent order and harmony separate from humans,

or is it now conceptually and practically hybrid, interwoven with humanity?

Is environmentalism about saving nature to you? If so, what sort of nature do you wish to be saved: wilderness? habitat? gardens? golf courses? Nature takes all kinds of forms, some of which you may prioritize more than others in your environmental concerns. We each define nature in our own way, including some things and excluding others. Many of us believe that it’s important to realize that we are a part of nature, but what exactly does this practically mean? The EcoTypes Nature axis allows us to explore our assumptions about nature, via pure vs. hybrid poles highlighting an important distinction scholars have observed in how we make sense of nature.

Ideas of nature can be found among a wide range of popular environmental concepts; consider for instance how “sustainable” and “natural” are often interwoven, such as in The Natural Step organization. Reflecting more deeply on what we mean by nature, then, may help us craft a more thoughtful approach to environmentalism.

More broadly, ideas of nature have played a key role in western civilizations for centuries (Glacken 1967); indeed, nature is one of the most culturally laden notions in the English language (Williams 1980) with a variety of uses and critiques in academic scholarship (Castree 2005). Think of how “natural” or “unnatural” are used in a variety of popular contexts, including but not limited to environmental issues. Do you prefer natural ingredients in your breakfast cereal? A natural treatment for headaches? Are certain forms of sex unnatural? Is working under fluorescent lights unnatural? Nature is clearly not a morally neutral term, then, in everyday discourse; yet the moral goods and bads connoted by nature are arguably a product of culture, not of some moral anchor residing outside of culture.

One key difference among scholars concerns pure vs. hybrid approaches to biophysical nature. A good deal of North American environmentalism has been grounded in notions of nature that emphasize its order and harmony, often in contrast to the human realm; witness, for instance, the significance of wilderness protection. As one looks a little deeper, this notion of nature emphasizes purity vis-à-vis humans (cf. White 2000): as the 1964 Wilderness Act stated, wilderness is “an area where the earth and its community of life are untrammeled by [humans].” The idea of purity in nature goes far beyond wilderness: common slogans around minimizing our environmental impact, for instance, often presuppose that all such impacts are negative, compromising nature’s pure state. Purity carries considerable force in environmentalist outreach: the old growth forest, the rushing stream of clear water, the rolling grassland. These become iconic nature worthy of our defense, because they appear not to have been touched by humans.

Yet over the last several decades, many scholars have modified, challenged, or rejected this pure view of nature. They do so based on two related claims, one about reality and the other about how we represent this reality. Our biophysical world, they argue, is entangled with human actions, such that what we might think of as untouched has in fact been modified by humans. So, we might think of a forest as natural, but in fact the tree species that constitute the forest have long been shaped in part by Indigenous use of fire, then by fire suppression by later settlers. In a deeper sense, our very ideas of nature, as suggested above, are cultural and political constructions, these scholars say—a position sometimes called constructivism. So, when we talk about nature or impute good qualities to nature, we are actually projecting our culture onto nature. Once, for instance, the term wilderness meant a foreboding, desolate, even scary place; more recently, wilderness often implies a calm, beautiful, peaceful place (Cronon 1995a).

Scholars critical of a pure nature offer a more hybrid and relational view, one that strives to avoid essentialism—the notion that things have a fixed, shared essence. Scholars advancing hybrid notions of nature challenge essentialist assumptions of nature as, for instance, in equilibrium until humans disturb it (Holling 1973), or as a benign, harmonious force shaping the world (Glacken 1967). The endpoint of this hybrid approach to nature may in fact be one in which very term “nature” disappears (e.g., Latour 2004), given its questionable ontological status and mixed political import.

These arguments have typically been met with resistance. As one example, a variety of publications (e.g., Lynas 2011; Shellenberger and Nordhaus 2011; DeFries et al. 2012) endorsing the notion of the Anthropocene, a view of Earth as fundamentally shaped by humans, have met similarly fierce opposition (Wuerthner et al. 2014; Wilson 2016; e.g., Proctor 2013; Dalby 2016). And as a final example of conflict over the concept of nature, the early collaborative scholarly project “Reinventing Nature,” summarized in the book Uncommon Ground (Cronon 1995b), was challenged in another book, Reinventing Nature?: Responses to Postmodern Deconstruction (Soulé 1995). It seems that scholarly debate over pure vs. hybrid nature is not going away!

Though scholarly literature exploring pure vs. hybrid Nature poles is now well established, the debate may not enjoy similar recognition in popular environmental discourse. Many people recognize that, for instance, nature can be a garden as well as wilderness. But the potential ramifications of a pure vs. hybrid approach to nature go far beyond that of more vs. less humanized landscapes. Taken fully, challenges to longstanding cultural notions of nature as pure may lead to entirely new ways of approaching environmentalism and environmental scholarship (cf. Proctor 2009a; 2016).

Science

Should we trust alternative claims to truth, or those of established science, when seeking environmental facts?

Do you keep abreast of science? When you make a decision affecting your personal health, do you try to follow the recommendations of medical science? How about environmental issues: do you see yourself as following the findings of scientists? Most of us tend to believe that we follow the facts on important issues affecting our lives and the planet. Yet science is only one source of facts today, and we may or may not feel that scientists are the most authoritative source. You may trust the experiences of a certain group of people; or the truth claims of certain political or spiritual leaders; or simply someone on social media you follow. The EcoTypes Science axis lets you explore these various claims to truth via its poles of orthodox, established science vs. a host of alternative, heterodox sources of facts.

Science has a prominent though convoluted relationship with environmentalism. On the one hand, the positions of environmentalists and environmental organizations are often advanced as firmly grounded in scientific research and related facts. One classic example is the book and movie An Inconvenient Truth (Gore 2006), in which the scientific facts of climate change are presented as a truth that decisionmakers often avoid due to their inconvenient political repercussions. Indeed, scientific consensus on the reality, severity, and human causes of climate change is extremely strong and well publicized (Oreskes and Conway 2010). It would seem that environmentalism, then, is without controversy among scientists, and that anyone who takes scientific evidence seriously would be on the side of environmentalists.

This view is complicated, however, in several ways. One involves critiques of scientific objectivity (e.g., Haraway 1988), along the same constructivist lines as noted above among scholars of nature. Constructivists argue that supposed facts are culturally constructed; thus science is less an objective authority than a product of certain people in certain places and times—a claim examined in various contexts via science and technology studies. Or, following a milder reading, many scientists are well aware that their current extent of knowledge is limited, and would be cautious claiming authority on “the facts”—indeed, most scientists would not equate science with some accumulation of settled facts.

As another important complication, empirical findings suggest that the views of many people, including environmentalists, are frequently at odds with scientific consensus (Pew Research Center 2015): examples include GMOs, pesticides, and nuclear power. In all such cases, members of the American public are far more skeptical than scientists. As one example, 37 percent of Americans believed that it is safe to eat genetically modified foods, as compared to 88 percent of members of the American Association for the Advancement of Science. So, it may not be entirely true that all environmentalist claims are grounded in scientific findings, though indeed some are.

More broadly, some scholars question whether science-based environmental communication is effective. They argue that misunderstanding may not be the problem; or, if misunderstanding exists, it may not be effectively addressed via conveyance of facts (e.g., Wynne 1993). So, even if a great deal of environmentalism is grounded in scientific findings, it may be a mistake to convey environmental concern via lists of scientific facts.

Yet many of us do indeed ground our environmental positions on certain facts—whether or not these facts are in accordance with communities of science. For purposes of simplicity, the EcoTypes Science axis contrasts two poles, two sources of authoritative facts: established, orthodox Science—essentially, the factual consensus among professional scientists—vs. alternative or heterodox claims that either seem to go beyond what scientists are comfortable claiming, or that actually contradict a good deal of mainstream science. No matter how well established environmentalism seems to be in orthodox science, heterodox science is hugely influential as well.

Those among us who cite orthodox Science as an authoritative source of facts about not only climate change, but biodiversity loss, toxic pollutants, and other important environmental issues, are for the most part doing so legitimately. Yet many also tend to cite orthodox Science to support their opposition to nuclear power, biotechnology, and other areas where scientists actually diverge from environmentalists. And heterodox Science—factual claims not well established in the scientific community—plays an important role in environmentalism as well. The heterodox Science pole is quite mixed, ranging from people sympathetic to the truth claims underlying New Age nature spirituality and paranormal phenomena (Hess 1993), to those who flatly disbelieve in the authority of mainstream science—perhaps best known in the case of climate change denial (Dunlap and McCright 2011)—all of whom claim some scientific validation for their approach.

In an even broader sense, the mounting phenomenon of post-truth suggests that heterodox claims have risen in public discourse. Post-truth is best understood not as a series of falsehoods, but of growing skepticism regarding the possibility of truth, and one source of this skepticism may be the clear contradictions we hear between orthodox and heterodox Science. We have all heard these contradictions in political proclamations and the global COVID pandemic, but post-truth arises in environmental contexts as well, such as when climate change is presented in wildly differing ways, or the substances we are exposed to or eat are framed as scaringly toxic vs. perfectly healthy. An understandable public response, then, may not be to trust orthodox or heterodox Science more, but to give up on truth entirely.

Perhaps there indeed are many legitimate ways to ground our environmental truth claims, given multiple, possibly incommensurable dimensions of reality, as philosophers such as Nancy Cartwright and Paul Feyerabend have variously claimed (Cartwright 1999; Feyerabend 2020). On this generous interpretation, orthodox and heterodox Science are simply different, not contradictory. But environmental discourse challenges this generous interpretation, as truth claims are often adjudicated in terms of whether or not they “follow the [orthodox] science,” or whether their heterodox derivation is tantamount to bad irrationality. The orthodox vs. heterodox Science poles offer an opportunity for us to explore this important tension, and to think more clearly about our sources of truth.

Social Scale

Can individual-scale practices make an ecological difference, or should we focus on key institutions?

Each of us may do things as individuals because we feel they are the right things to do. In the environmental realm, for instance, perhaps we don’t litter, or we do recycle, even if we know that others may or may not do these things as individuals. But we may worry that they don’t really make a difference, because each individual does make their own choice, and many may choose otherwise. Thus, we may suspect that we need to work collectively for action at larger, institutional scales that affect all of us, like the policies, laws, and norms that govern or guide our behavior.

The EcoTypes Social Scale axis allows us to reflect, via its individual vs. institutional poles, on our most effective actions. The Social Scale axis resembles the Change axis in helping us think about effective change, but it departs from Change by focusing on the scale (individual/institutional) vs. rate (incremental/radical) of change. Like Change, Social Scale reminds us that there may be fundamental differences in our assumptions as to how we might most effectively address issue of environment.

A great deal of mainstream environmentalism stresses the little things we each can do: the products we purchase, our transportation choices, whether we recycle or turn off the lights, etc. Of course, these little things are insignificant in light of our global environmental condition, but if enough people do these practices perhaps they can make a big difference. There is an opposing position: that these small lifestyle choices actually do little more than make us feel good. According to this position, if we really want to attain positive environmental change we need to work together in civic, political, and other shared contexts to help change or enforce laws, ensure optimal policies, and otherwise focus on collectively binding practices, not individual practices.

This important debate is, then, one of the appropriate social scale of environmental action: whether, in brief, individual or institutional-scale change is where we should put our time and energy. It is, of course, easy to say “Both!”…but, in practice, one cannot do everything, and one wants to do what will make the biggest difference. So the Social Scale EcoTypes axis encourages us to consider carefully the scale of our action and its practical efficacy.

There is an abundant popular literature pointing out the many individual-scale actions we can do. For starters, simply search for “simple things save earth ” and you will find a wide range of online lists, also available in book format for adults and children (e.g., Javna et al. 2008; Javna and EarthWorks Group 2009). And individual-scale action can potentially make a larger difference, for instance via the notion of a tipping point (Gladwell 2000), where a critical mass of small actions leads to large-scale adoption of these actions. The individual Social Scale pole generally supports the incremental pole of the Change axis introduced above, in that change would happen bit by bit; but, possibly, individual-scale action resulting in a tipping point might actually lead to nonlinear, radical Change as well.

For the most part, however, many scholars are less convinced of individual-scale action than the popular press, favoring more institutional-scale action (Steinberg 2015). As one representative critique, Michael Maniates says:

When responsibility for environmental problems is individualized, there is little room to ponder institutions, the nature and exercise of political power, or ways of collectively changing the distribution of power and influence in society—to, in other words, “think institutionally” (p. 33).

Critiques of individual-scale action can also be found in the abundant literature on neoliberalism, referring to a privatization of environmental responsibility and reduction in emphasis on public-sector efforts and related politics, for instance in the context of sustainability (Swyngedouw 2010; Cock 2011; cf. Proctor 2010). According to these critics, individual-scale actions of the “50 Things” variety are exactly what neoliberal regimes do to distract us from necessary collective political action.

Institutional-scale action need not only address institutions such as neoliberalism decried by the political left. In sociology, institutions are generally defined more deeply as collective, structured rules or norms; thus, families or language, and everyday environmental practices such as recycling services and transportation choice, are patterned and enabled by social institutions, and institutional-scale action may also address such mainstream entities. The tension between the individual vs. institutional Social Scale pole is thus not necessarily one of politics, though it is true that institutional-scale change is generally more often championed by environmentalists on the political left.

Social scale is related to other expressions of scale, such as spatial scale. You have probably heard the classic environmental phrase “think globally, act locally,” which like many expressions of individual Social Scale has generally been questioned by scholars, some of whom argue we actually have a moral obligation to “act globally,” i.e., to help people throughout the world, as we have among those in our local community (Singer 1972; 2004). Others argue for a cosmopolitan politics, noting that the key challenge we face is a world of difference coupled with interdependence. Thus, environmental issues such as climate change demand more than local-scale actions, in fact reveal a global, “…‘cosmopolitan imperative’: cooperate or fail!” (Beck 2006, 258). Others such as Ursula Heise (2008) have gone farther to argue that local-scale environmentalism may fall prey to reactionary, nationalist political tendencies—that only an “ecocosmopolitanism” will adequately address the ecological challenges of late modernity. Social and spatial scale are not exactly the same, but in general the institutional Social Scale pole refers to action at bigger spatial scales as well.

More broadly, the tension between individual and institutional-scale action reflects a general discussion in sociological theory between the relative role and significance of agency vs. structure in shaping our social world, where the resolution may be that both play a role in some interactive manner, a theory known as structuration (Giddens 1984).

Does structuration challenge the reality of these individual vs. institutional Social Scale poles? It does remind us that individual-scale actions are structured at institutional scales, and that these institutions are reproduced or challenged via individual-scale action. Nonetheless, the preponderance of calls for individual- or institutional-scale environmental action suggests that the Social Scale axis remains an important one to consider as we consider our differing ways of approaching environmental issues. Do you carry a shopping bag or ride your bike to make a difference? Do you struggle alongside others to change big systems preventing environmental progress? (And if you do both, which in your mind is most effective?) Calls for individual- and institutional-scale action are everywhere in the environmental realm, as these Social Scale poles remind us.

Society

Should environmental action build on social consensus, or is it better to assume that social difference and conflict are inevitable?

Society: what does that word mean to you in an environmental context? Say, if you heard someone say “Society needs to give up its wasteful use of energy if we are going to solve global warming,” would you agree? And who exactly is “society,” anyway? Is it all of us equally? Is it some people—those in power, or those who consume most—more than others? The EcoTypes Society axis allows you to explore our differing assumptions about society, via its consensus and conflict axes summarizing two classic approaches.

One crucial yet often overlooked dimension of environmental issues involves our assumptions about social relations. This EcoTypes axis addresses a classic divide in sociological theory, that between consensus and conflict views of society. Though the debate over consensus and conflict theories peaked in sociology perhaps a half century ago (Bernard 1983; Manza et al. 2010), it remains deeply relevant to our understanding of environmental movements and the environmental policies we prioritize.

What two theories of society are implied in the consensus and conflict poles? Consensus theory posits that, in general, societal norms and institutions arise from the interests and desires of the people who constitute that society; in contrast, conflict theory views society as a realm of contestation and power differentials, where prevalent social institutions, laws, and policies emerge not from the consensus of the many but the powerful interests of the few, or from the result of conflicts between social groups. One would imagine that both consensus and conflict define most societies, and contemporary sociological theory pays attention to both; but in its day (e.g., Horowitz 1962; Scheff 1967; Lipset 1985) the conflict/consensus binary, championed by eminent sociologists such as C. Wright Mills, offered a convenient and important distinction, and our assumptions on how to address environmental issues often involve related assumptions of conflict or consensus Society.

To consider the potential relevance of the EcoTypes Society axis, let’s reflect on one example: how shall we best deal with air, water, and solid waste pollution? According to the consensus model, pollution arises largely from our collective contribution (whether directly, e.g., by driving cars or dumping waste, or indirectly, by consuming polluting products), and the laws that deal with pollution likewise arise from our collective input (by voting for/against laws, electing government officials that pass laws, etc.). If pollution is a problem, then all of us are in part to blame, both for causing this pollution and for failing to pass adequate laws and enforce policies that will deal effectively with pollution. Thus, the consensus view of society suggests that effective pollution control requires greater public education about its importance, and marshaling public support for laws and policies that encourage all of us to pollute less.

As sensible as the consensus view may appear, other accounts of pollution thoroughly call it into question, supporting a conflict model of social relations. Consider the work of one sociologist, William Freudenburg, who posited a “double diversion” that largely masks the conflict and power differentials behind natural resource exploitation and pollution, presenting a false front of consensus (Freudenburg 2005; 2006). This double diversion, according to Freudenburg, involved (a) disproportionality, whereby a privileged few have access to natural resources and are allowed to contribute the bulk of pollution, along with (b) distraction, whereby this inequality is hidden, thus a more consensual notion of natural resource use and pollution appears reasonable. To scholars such as Freudenburg whose work presumes a conflict model, consensus model approaches to pollution control simply continue to mask their true nature; what is needed instead is direct confrontation of the inequities that underly continued pollution by powerful corporations, and support for the poor and powerless who often face disproportionate impacts of pollution.

Consensus vs. conflict Society poles also imply differing takes on environmental conflict as summarized above. Why are environmental battles so heated today, and what can we do about these battles? By assuming the possibility of social agreement, a consensus-based approach would seek means to restore agreement, possibly in some form of compromise among all battling parties, say in disputes over forest management or pollution control. The conflict approach, however, finds environmental conflict to illustrate a power struggle, often involving subjugated peoples fighting for some control of essential natural resources or other critical environmental needs. In this view, conflict is not resolved by agreement, but by seeking fairer sharing of power among conflicting parties—and given the reluctance of people in power to let go of power, these conflicts may not go away quickly.

Some environmental movements are largely built on a conflict model of society, such as environmental justice. On a scholarly front, political ecology (e.g., Robbins 2012) is also built on more of a conflict model, given its indebtedness to political economy and focus on differential power relations. As one example of a diffuse, largely consensus-based movement, sustainability has been challenged by scholars who similarly reframe it via the lens of conflict (Swyngedouw 2010; Weaver 2015; Frank 2016); more broadly, then, environmentalism itself can be built on either consensus or conflict models, with divergent visions of a desirable future (Pepper 2005).

Whatever one’s inclination toward consensus vs. conflict Society, it seems that more careful attention to our assumptions about social relations and power is worthy of our attention (Maniates and Princen 2015). The Society axis is one of several that reminds us ways in which our environmental worldview includes considerations most people would not think of as environmental, yet assumptions of consensus and conflict may be just as important as our assumptions regarding axes such as Ecosystems or Nature above.

Spirituality

Is it best to approach environmental issues from a sacred perspective or a secular perspective?

Would you describe yourself as spiritual and/or religious? Even if you wouldn’t, do you feel that spirituality may offer important environmental insights? Or, do religion and spirituality have little to do in the environmental context, or possibly even detract from rationally analyzing and solving environmental problems? The EcoTypes Spirituality axis, via its sacred vs. secular poles, offers us an opportunity to reflect on these differing takes as to the role of religion and spirituality in the context of environment.

Spirituality is popularly regarded as separable from religion: some people call themselves spiritual vs. religious to describe a devotion that is more individualized, authentic, and less institutionalized. Not all scholars, however, make such a clear distinction, as what many think of as their own private spirituality may share many features in common with others, and the concept of religion has been stretched by scholars far beyond institutional religion. The EcoTypes Spirituality axis thus subsumes the broad realm of religion and spirituality.

The prevalent story of environmentalism is that it is grounded in the facts of environmental degradation as revealed by science. Yet for many people, the nonhuman world is understood in spiritual, sacred terms (cf. Eliade 1959). There is thus a different way to understand environmental concerns, as arising more from religious and spiritual sentiment than from scientific fact (Proctor 2009c; 2009b). Indeed, the history of North American environmentalism involves religious and spiritual as well as scientific roots (Albanese 1991; Worster 1994; Taylor 2010).

This spiritual thread underlying environmental concern is clarified in part via attitudinal surveys, which minimally suggest that religious belief does not necessarily detract from environmental concern (e.g., Kanagy and Nelsen 1995; Proctor and Berry 2005; Morrison et al. 2015). More positively, a belief in the sacredness of nature (whether inherently sacred, or because it was created by God) is in fact a strong predictor of environmental concern (Proctor and Berry 2005; Proctor 2009c).

Scholarly discussions around spirituality and environment are often grounded in the classic thesis of Lynn White (1967), in which he argued that responsibility for environmental degradation lay squarely in western Judeo-Christian religious traditions. White’s thesis put into motion a long period of scholarly reflection as to whether religion and spirituality have played, or can play, positive or negative ecological roles (e.g., Dubos 1980; Taylor et al. 2016). The sacred vs. secular Spirituality poles are thus both represented in scholarly literature.

Further reflection may suggest reasons why spirituality may not always be helpful in environmental contexts. For instance, nature spirituality may work well for environmental issues such as old-growth forest protection, where ancient forests can readily be seen as sacred, but what about the many other environmental issues where notions of pure nature, often assumed in nature sacredness, are less applicable (Proctor 2009c; see also Nature axis summary)? More broadly, a focus on spirituality may reinforce a vague idealism, ultimately neglecting material forces responsible for environmental problems and arguably central to solutions. Or, possibly, apocalyptic tendencies may result (Pepper 2005; Shellenberger and Nordhaus 2011; Swyngedouw 2013; cf. Albanese 1993; Proctor and Berry 2011). Indeed, apocalyptic environmental futures, so common in climate discourse today, are arguably derived more from environmentalism’s heritage in religion than in science. The secular Spirituality pole may be summed up by pronouncements that nature spirituality detracts from science and rationality (Ehrlich and Ehrlich 1996).

In a broader sense, then, the Spirituality axis invokes a complex history of interaction between religion and science, one in which conflict between the two was never the full story but also amply evident (Proctor 2005). One summary suggests Conflict, Independence, Dialogue, and Integration as four possible ways of relating religion and science, where Dialogue and Integration may support the sacred pole of Spirituality, and Conflict (and to some extent, Independence) the secular pole (Barbour 2013). As examples, Ken Wilber’s Integral Ecology offers one theoretical justification for approaching religion and science as ultimately one (Esbjörn-Hargens and Zimmerman 2009; Zimmerman 2009); Stephen Jay Gould’s Non-Overlapping Magisteria (Gould 1999) suggests that the two are important, but distinct (and thus spirituality may be less relevant in an environmental context than science); and many book-length critiques of religion such as God is Not Great (Hitchens 2007), The God Delusion (Dawkins 2006), and Infidel (Ali 2008) leave little room for the place of spirituality in public life, including matters of environment.

This larger context of religion and science reminds us that, no matter what our personal take, there are differences out there in how people might approach the relevance of Spirituality to issues of environment: some may find it absolutely crucial (sacred Spirituality), while others may find it less important, possibly even distracting or harmful (secular Spirituality). Whether you support the sacred or secular pole on the EcoTypes spirituality axis, it may thus be important to consider how religion and spirituality affect the environmental ideas we and others have, and what may be the proper role of these spiritual impulses in guiding our environmental beliefs and practices.

Technology

Should we be afraid of technology in context of environmental issues, or should we welcome technological solutions?

There is a lot you probably hear about technology, perhaps in the context of digital devices, or transportation, or medicine, or a host of human interests and concerns. How does technology make you feel? Are you hopeful that technology will successfully address some of humanity’s biggest challenges? Are you amazed, possibly alarmed, at how quickly technology changes? And when you hear of technology potentially helping clean up pollution, or sequester carbon, or help monitor species conservation, are you happy at the prospect, or do you worry that people are just creating more problems by throwing technology at environmental problems? The Technology axis, and its philic (loving) vs, phobic (fearing) poles, is an opportunity to explore how we approach technology in an environmental context.

Environmentalism has long been ambivalent about technology. Take energy production, for instance: on the one hand, images of wind generators and solar panels commonly appear on campus and corporate websites advertising their green commitment, yet on the other, images of coal and nuclear power plants are used by environmental organizations to represent grossly polluting or risky technologies, and environmentalist support for “clean” or “green” wind and solar power is often as passionate as their profound concerns regarding coal and nuclear. Indeed, this ambivalence suggests that not all environmentalists would fully ascribe to the above!—as one example, see the pro-nuclear environmental organization Environmental Progress.

How shall we understand our attitudes toward technology in the context of environmental issues? Let’s examine the root of the word to get a deeper sense. As elaborated by ancient Greeks as well as modern philosophers such as Heidegger (1977), the word techne, meaning skill or craft, is understood as the opposite of physis, the Greek word for the self-generating mechanisms that defined their view of nature. Environmentalist ambivalence toward technology perhaps thus goes way back, as in an etymological sense technology is unnatural. Does this imply that technology inevitably detracts from environmental progress—that we should continue to fear technology as a monstrous imposition on our green Earth? This is the pole of technophobia. Or, is technology not only essential to environmental solutions, but even a celebration of human creativity in working alongside the nonhuman world? This is the pole of technophilia.

Supporting this ambivalence has been a wide range of scholarly opinion on technology and environment. Barry Commoner, for instance, expressed concern over unfettered deployment of polluting technologies by corporations (Commoner 1971), whereas Ian Barbour offered a range of values choices to guide our use of technology in the context of environment (Barbour 1980). In a broader context, Donna Haraway challenged the very distinction between techne and physis in embracing a mix of the two (Haraway 1991), and Bruno Latour approached technology not as a monolith but as the outcome of a fragile network of relations between people and things (Latour 1996).

Ambivalence regarding technology is not at all limited to environmentalists; popular opinion reflects this mixed attitude as well. In one survey (Pew Research Center 2014), Americans were shown to be generally positive in their hopes that technology will improve the human condition in future, while worrying about certain technologies in particular such as designer babies and robots. And, as noted in the Science axis summary, the American public deviates from scientific opinion on certain environmental technologies such as GMOs or nuclear power (Pew Research Center 2015). These attitudes about technology are place-specific: for instance, Americans and Europeans differ markedly in their concerns related to these technologies, and people from various European countries differ among themselves as well. Ambivalence thus means difference and debate in the context of technology, as surveys have consistently demonstrated.

Recent developments in technology seem to feed on, and exacerbate, this ambivalence, with some of us more celebratory and others among us more worried. One good recent example is AI, or artificial intelligence. We are hearing that AI may help us by creating more incisive, detailed answers to digital searches; but we are also hearing that it may effectively wipe out many of our existing jobs due to its advanced textual abilities. We see AI-generated images that suggest all sorts of creative possibilities for art and entertainment; we also see AI-generated images that suggest how readily it might be employed to manipulate people into believing falsehoods regarding popular starts and political leaders. Though discussions of AI are not usually tied with issues of environment, AI will arguably transform our understandings, concerns, and solutions in the environmental realm as well. Do new, in many ways unknown technologies such as AI prompt in you a phobic or a philic stance?

The EcoTypes Technology axis thus represents one of the more visible differences in ways we care about issues of environment. We may all deeply wish to effectively address, say, toxic pollutants affecting low-income neighborhoods, or the effects of climate warming on nonhuman habitats; but are we okay with technology playing an important role in addressing these issues? Or, did technology play an important role in leading to such problems, and if so, why would we think it help solve them? Whether you tend to be technophilic or technophobic, you can see that the Technology axis has a rightful place in helping us understand our differences.

Time

Should we look back to more harmonious times in past to find environmental solutions, or is it best to move into the future?

Some people worry that we have lost important traditions and practices from the old days; are you like this? Do you feel that so-called human progress is taking us farther and farther away from better times in past? Or maybe you feel exactly the opposite: that the past was a time minimally of inconvenience and mere survival, perhaps even of repression and outright violence, and we should celebrate human progress over time. These orientations may apply for you to issues of environment as well: do, say, Indigenous peoples offer important guidance given their longstanding land practices and traditional wisdom, or do you place greater weight on humanity’s continued discoveries, ingenuity, and innovation? The EcoTypes Time axis, the last of twelve EcoTypes axes, offers an opportunity to consider our inclinations via its past vs. future poles.

In many respects, environmentalism appears primarily oriented toward the future: take, for instance, dire warnings about climate change impacts or global biodiversity loss. It may be possible, however, to approach various forms of environmentalism based on a past vs. future orientation to time. What exactly would a past vs. future orientation look like? One key distinction contrasts conservative and progressive approaches to time. Based on the broad philosophy of conservatism, the conservative approach seeks to recover, return to, or otherwise honor past realities or institutions. In distinction, the progressive approach, itself based on a broad philosophy of progressivism, places more faith in improvement of realities and institutions over time, i.e., progress, and thus is future oriented.

Environmental examples abound. Classic biodiversity conservation, for instance, has focused on recovering a past we have largely destroyed; and current efforts, from ecological restoration to rewilding, use the past as their guide and goal. On the other hand, climate change poses an uncertain future, one we suspect we cannot successfully address from our experiences and wisdom of past. How do we deal with sea level rise, increased flooding, heat waves, wildfire? Taken together, this combination of threats is unknown in our collective global experience; we face them knowing we may well need to create new institutions, new technologies, new ways to cope with uncertain futures. These examples do not do not imply that particular issues—say, conservation or climate—are always approached via a past vs. future orientation, but that past- and future-oriented environmentalism is amply evidenced via the issues for which many of us care—as one example, the U.S. conservation movement could either be described as conservative or as progressive (Hays 1959)!

Let’s first focus on a past-oriented approach, as conservatism may sound like a surprising outlook to link with environmentalism. Our interest here is not purely with conservative political movements, though an argument for green conservatism has been made (Scruton 2012). A focus on the past resonates with what has been typified as social (vs. economic) conservatism (Everett 2013), in some ways a broader resistance to change evidenced in a range of conservative attitudes (Jost et al. 2003). More broadly, a range of back to the land impulses among contemporary urban environmentalists reflect this conservative, past-honoring orientation (Gould 2005). The contemporary back to the land movement resonates with the reverence some have for Indigenous peoples, their ways of living on the land, and their long history of experiential wisdom. Thinking of Indigenous knowledge as superior to modern science and technology is another expression of conservatism, of a past orientation, even though those who most honor Indigenous peoples may be from the political left.

Conservatism is an understandable response to the relentless change, disruption, and uncertainties of modernity (Berman 1983; Bauman 2000; Inglehart and Baker 2000). Conversely, one strong expression of a future-oriented, progressive approach to time is what has been known as ecological modernization (Spaargaren and Mol 1992; Buttel 2000; Mol and Sonnenfeld 2000; Fisher and Freudenburg 2001). Ecological modernization, in brief, represents a progressive approach by advanced industrial societies via economic, cultural, and political developments that result in technologies, political capacity, and popular support for improvement of environmental conditions over time. One environmental movement representative of certain elements of ecological modernization is ecomodernism. Ecological modernization is, however, but one hopeful trajectory, as even those broadly supportive of modernity have spelled out its limitations and risks (Latour 1993; Cohen 1997). And for every progressive environmental publication outlining opportunities for positive change in future (e.g., DeFries et al. 2012), there is another warning of the disruptive changes we need to plan for in future (e.g. Benson and Craig 2014)).

The above has suggested that past vs. future Time cannot be readily pared by political orientation, no matter how the words “conservative” and “progressive” resonate with the political right and left. It is true that a number of recent populist movements on the political right honor, and seek to recover, the past, but movements on the left increasingly honor the tradition of oppressed groups such as Indigenous peoples. Likewise, a future orientation may be found among those on the political right who call for increased globalization and market penetration of the world, while those on the political left may imagine broad deployment of advanced solar and wind renewable technologies in their utopian future.

The EcoTypes Time axis asks us to carefully examine our approach to issues of environment for the ways they may move forward or backward in time. In many cases we are effectively choosing the future, or choosing the past, as our reference point in addressing environmental issues. We are all now at the meeting point of past and future; how we weigh the two, in the context of environment, may bring out important differences in our orientation toward time.

Connecting the twelve axes

After reading these twelve axes, which proved the most surprising? the most informative? the hardest to understand or appreciate? You may have a variety of reactions to the twelve EcoTypes axes, but one helpful exercise may be to draw your own, intuitive connections between axes. In what ways do some axes sound related to each other?

Here’s an example: one of the first axes is Change, and one of the latter axes is Social Scale. As mentioned above, incremental vs. radical Change and individual vs. institutional Social Scale seem to be related, in that individual-scale action effects change at an incremental rate, but institutional-scale action may effect change in a radical, sweeping manner. This may not always be true: it is, for instance, possible that institutional-scale change, say a change in fuel economy standards, has an incremental effect on emissions due to its phase-in provisions. But there is clearly something about these two axes that may jointly affect how we respond to them, so that if you believe in radical Change you may also well believe in institutional Social Scale.